Historical Note for SUB ROSA - SANCTUARY'S END

The setting of this novel is a time and place which has long held a deep fascination for me, and about which I have read dozens and dozens of books over the years—from Roman history, religious history, theology, ancient philosophy, archaeology, the Bible, and more. It is the era when Early Christianity was struggling to achieve critical mass against the currents of competing ‘pagan’ religious beliefs. Just as importantly, it was a period where the competition of which version of Christianity would win out over others—and why—was being decided. More than any other place during this epoch—including Rome, Constantinople and Jerusalem—Alexandria was at the very hub of it all, a center of and convergence point for all the religious and philosophical beliefs of the Western World. Here, Jewish, Roman, Greek, Ancient Egyptian, Christian and rich Middle-Eastern systems of thought and religious belief were part of the vital currency of the place. And with the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, everything changed. It is my hope that while scholars in theology may challenge certain perspectives expressed in this book, that scholars of religious and ancient history might acknowledge and accept the feasibility of the story’s framework.

One of the observations which struck me in my readings was the remarkable difference of persistent and popular perceived history versus the actual written record. One example: most people, some eminently educated and who cite it in their writings, state that Jesus Christ’s trade as a young man was a carpenter. This precise term is found nowhere in the original source text of the New Testament. That label is rather a tradition with possibly seismic implications. Instead, the Gospels in their original Greek use the term tekton, which can indeed mean ‘carpenter’, but numerous scholars would submit the more common and logical translation is ‘mason’ or ‘builder’, since there was very little wood in this region for a carpenter’s craft, but plenty of stonework building projects being performed for both Romans and local Jewish needs in this vital Roman colony. For Jesus to be of the venerable House of David, being in the family of a builder, in the tradition of freemasonry and Solomon, would make more sense than being the son of some obscure backwater carpenter. This translation of the term, however, is studiously avoided, because of its suggestion that Christ might have been educated in a Masonic tradition, whose roots go back to ancient Egypt, and some scholars (citing the Book of Enoch) say before. Early Christian religious history is filled with many misconceptions, sanctified as tradition and, accepted as fact. My novel strives to reference some of these points within the larger story weave of a historical thriller.

All of the characters in the book—except one: Bishop/Pope Theophilus—are fictitious. Theophilus’s use of the notorious paramilitary monks, the Parabolani, is documented historical fact. Roman Emperor Theodosius’s edict against visiting and worshiping pagan temples, and its widening enforcement, occurring exactly at this time, is also documented history. I also drew from the documented tradition of the enigmatic legacy of the House of Joseph of Aramathea, in whose tomb Jesus of Nazareth was interred after the crucifixion. The well-established historical tradition of Joseph of Aramathea outside the Bible is compelling, and provides persuasive insight into early Christianity in the British Isles, and elsewhere, before the Roman Church’s rigid, hierarchical and powerful influence arrived. What I strived to portray in this story—recognizing that over 180 versions of devout Christianity were alive and competing with each other for the hearts and minds of mankind at this time—was the challenge people faced in remaining true to their own genuinely pious religious beliefs which did not align exactly with the evolving orthodox Articles of Christian Faith, and despite the fact that they too considered themselves true followers of Yesu the Nazarene.

The setting of this novel is a time and place which has long held a deep fascination for me, and about which I have read dozens and dozens of books over the years—from Roman history, religious history, theology, ancient philosophy, archaeology, the Bible, and more. It is the era when Early Christianity was struggling to achieve critical mass against the currents of competing ‘pagan’ religious beliefs. Just as importantly, it was a period where the competition of which version of Christianity would win out over others—and why—was being decided. More than any other place during this epoch—including Rome, Constantinople and Jerusalem—Alexandria was at the very hub of it all, a center of and convergence point for all the religious and philosophical beliefs of the Western World. Here, Jewish, Roman, Greek, Ancient Egyptian, Christian and rich Middle-Eastern systems of thought and religious belief were part of the vital currency of the place. And with the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, everything changed. It is my hope that while scholars in theology may challenge certain perspectives expressed in this book, that scholars of religious and ancient history might acknowledge and accept the feasibility of the story’s framework.

One of the observations which struck me in my readings was the remarkable difference of persistent and popular perceived history versus the actual written record. One example: most people, some eminently educated and who cite it in their writings, state that Jesus Christ’s trade as a young man was a carpenter. This precise term is found nowhere in the original source text of the New Testament. That label is rather a tradition with possibly seismic implications. Instead, the Gospels in their original Greek use the term tekton, which can indeed mean ‘carpenter’, but numerous scholars would submit the more common and logical translation is ‘mason’ or ‘builder’, since there was very little wood in this region for a carpenter’s craft, but plenty of stonework building projects being performed for both Romans and local Jewish needs in this vital Roman colony. For Jesus to be of the venerable House of David, being in the family of a builder, in the tradition of freemasonry and Solomon, would make more sense than being the son of some obscure backwater carpenter. This translation of the term, however, is studiously avoided, because of its suggestion that Christ might have been educated in a Masonic tradition, whose roots go back to ancient Egypt, and some scholars (citing the Book of Enoch) say before. Early Christian religious history is filled with many misconceptions, sanctified as tradition and, accepted as fact. My novel strives to reference some of these points within the larger story weave of a historical thriller.

All of the characters in the book—except one: Bishop/Pope Theophilus—are fictitious. Theophilus’s use of the notorious paramilitary monks, the Parabolani, is documented historical fact. Roman Emperor Theodosius’s edict against visiting and worshiping pagan temples, and its widening enforcement, occurring exactly at this time, is also documented history. I also drew from the documented tradition of the enigmatic legacy of the House of Joseph of Aramathea, in whose tomb Jesus of Nazareth was interred after the crucifixion. The well-established historical tradition of Joseph of Aramathea outside the Bible is compelling, and provides persuasive insight into early Christianity in the British Isles, and elsewhere, before the Roman Church’s rigid, hierarchical and powerful influence arrived. What I strived to portray in this story—recognizing that over 180 versions of devout Christianity were alive and competing with each other for the hearts and minds of mankind at this time—was the challenge people faced in remaining true to their own genuinely pious religious beliefs which did not align exactly with the evolving orthodox Articles of Christian Faith, and despite the fact that they too considered themselves true followers of Yesu the Nazarene.

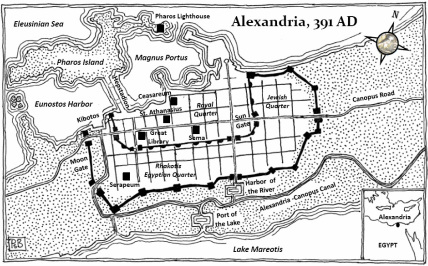

Additional elements which are based on historical research: the Pharos Lighthouse and its construction details; Nero’s emerald glasses; Alexandria noted as the birthplace of alchemy; the existence of the Sema—Alexander the Great’s tomb—which disappeared from history around this time; the Alexandrian zoo; the different districts of Alexandria, and the general layout of where the critical points of the city were. While many maps by well-intentioned contributors have been created through the years, they represent a broad range of possibilities. I have drawn my own, based on what makes the most sense to me, referencing dozens of sources, including a detailed archaeological survey of ancient Alexandria (The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, 300 B.C.–A.D. 700, by Judith McKenzie). The character Jacob Silvenus’s observations challenging prevailing Christian theological positions about Saints Paul and Peter are based on recent writings of researchers, scholars and religions historians (including Paul and Jesus by James D. Tabor and The First Paul by Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan).

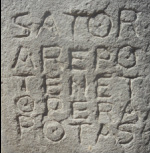

The enigmatic Sator-Rotas square—a Latin palindrome—is part of recorded history of this era, and its true meaning remains unsolved, though scholarly debates persist. The etchings on stone of this puzzle have been dated as early as 79 A.D. in Pompeii, found as well in Syria, England, Portugal, and more. It is associated with early Christianity before the tradition of the Roman Church. For me it is one more symbol of lost knowledge which remains unresolved.

The inciting action and the description of the events of the Serapeum are based on chronicled historical accounts of 391 A.D., including the striking down of the wooden statue of Serapis by a Roman horse soldier. The actual burning of the Library as an accepted date, however, is curiously, strangely, lost in history. A number of dates are cited for this event, yet none definitive… and yet for such a seismic occurrence, impacting world culture, it’s all quite murky. Some academics have conjectured that this lack of clarity in the historical record is purposeful. I cannot disagree. What makes sense to me is what is recounted in this story, because once the burning occurred the Dark Ages had indeed fundamentally begun for the Western World. With the essential knowledge of mankind lost, and the fall of Rome to the Visigoths a short time afterwards, the final death knell of this sphere of culture had sounded, and only the Roman Church dictated what knowledge was allowable for centuries to come. The Renaissance only began after wealthy Italian merchants—such as the De’ Medici—commissioned the search for and conveyance of ancient lost books from Arab countries to Europe and to facilitate their subsequent translations. From that point on, fueled by revolutionary knowledge and insight, it was a rolling thunder of innovation and invention which swept across Europe and the world. And with the continued discovery of lost texts from various sources, including the Nag Hammadi manuscripts and new manuscripts still being found and translated, I believe that age of discovery continues to this day. Our Renaissance continues as long as the knowledge is kept free for all.

The enigmatic Sator-Rotas square—a Latin palindrome—is part of recorded history of this era, and its true meaning remains unsolved, though scholarly debates persist. The etchings on stone of this puzzle have been dated as early as 79 A.D. in Pompeii, found as well in Syria, England, Portugal, and more. It is associated with early Christianity before the tradition of the Roman Church. For me it is one more symbol of lost knowledge which remains unresolved.

The inciting action and the description of the events of the Serapeum are based on chronicled historical accounts of 391 A.D., including the striking down of the wooden statue of Serapis by a Roman horse soldier. The actual burning of the Library as an accepted date, however, is curiously, strangely, lost in history. A number of dates are cited for this event, yet none definitive… and yet for such a seismic occurrence, impacting world culture, it’s all quite murky. Some academics have conjectured that this lack of clarity in the historical record is purposeful. I cannot disagree. What makes sense to me is what is recounted in this story, because once the burning occurred the Dark Ages had indeed fundamentally begun for the Western World. With the essential knowledge of mankind lost, and the fall of Rome to the Visigoths a short time afterwards, the final death knell of this sphere of culture had sounded, and only the Roman Church dictated what knowledge was allowable for centuries to come. The Renaissance only began after wealthy Italian merchants—such as the De’ Medici—commissioned the search for and conveyance of ancient lost books from Arab countries to Europe and to facilitate their subsequent translations. From that point on, fueled by revolutionary knowledge and insight, it was a rolling thunder of innovation and invention which swept across Europe and the world. And with the continued discovery of lost texts from various sources, including the Nag Hammadi manuscripts and new manuscripts still being found and translated, I believe that age of discovery continues to this day. Our Renaissance continues as long as the knowledge is kept free for all.